Acknowledgements

The Root Solutions for Public Safety project (including this publication series) is created in close collaboration with people across the country who have been impacted by mass incarceration including those working in the community, justice-system impacted people, and frontline government practitioners. This work has also been done in partnership with jurisdictions participating in the MacArthur Foundations Safety and Justice Challenge and engaging in a focused Racial Equity Project: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Cook County, Illinois; Pima County, Arizona; and New Orleans, Louisiana. We’d like to extend our gratitude to leaders from the organizations Why Not Prosper (Philadelphia), Total Community Action (New Orleans), CROAR (Cook County), and the YWCA of Southern Arizona (Pima County).

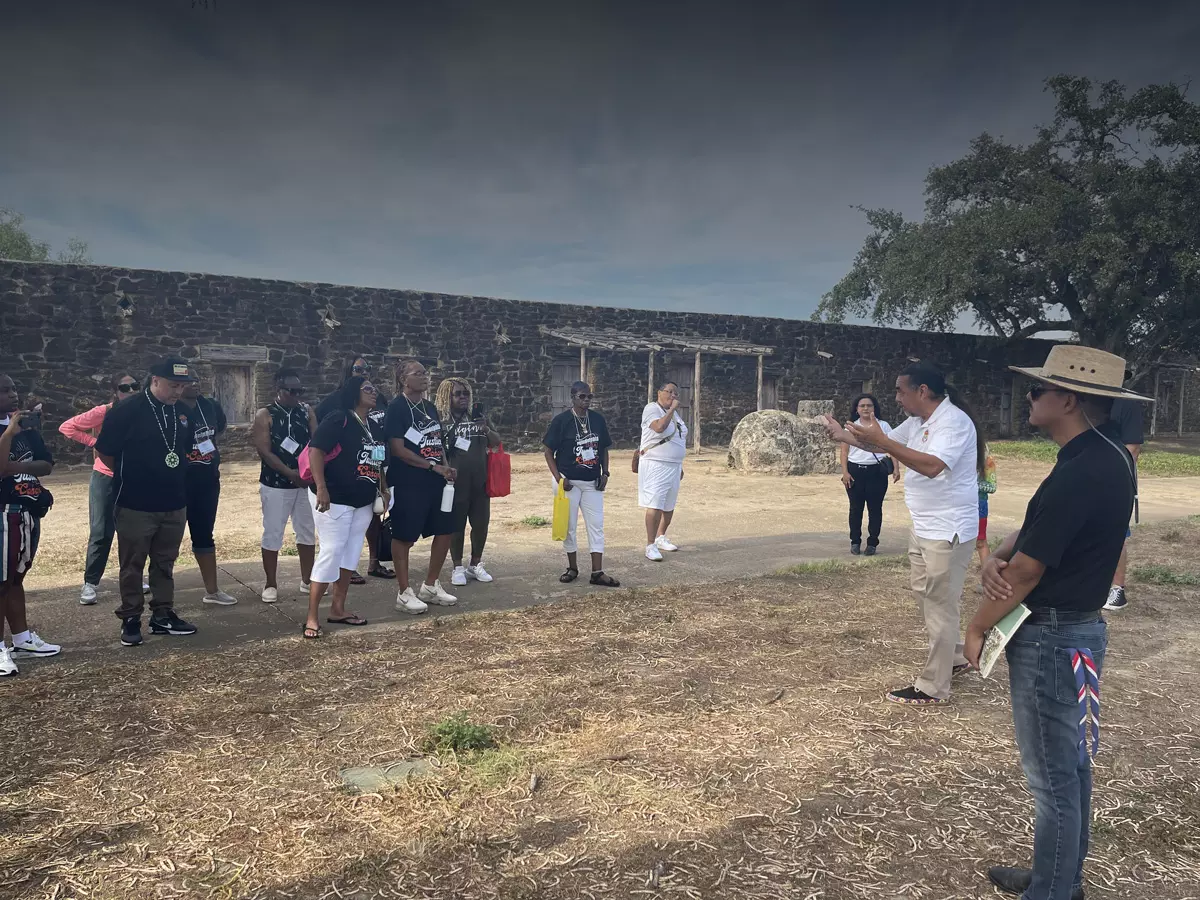

Thank you to the MILPA Collective and American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Mission (AIT-SCM) for your support and thought partnership in this project. And thank you to Olyvia Fabre, the talented graphic designer who brought this report to life.

Author: Alexandra Frank, Director of Root Solutions for Public Safety

Editors: Cathy Albisa, Everette R. H. Thompson- Francois, and Gordon Goodwin

Introduction

Building Root Solutions for Public Safety seeks to provide a platform sharing reflective pieces about the drivers of root solutions to mass incarceration while inspiring debate and discussion. Our commitment is to practice values of cultural healing and racial justice and feature content curated and crafted in partnership with justice-system impacted people, front-line government practitioners, and families. Our contributors will practice rigorous debate while offering practical and strategic solutions and analysis in service of advancing racial equity in the criminal legal system in the immediate term and ending mass incarceration in the long term.

Why launch this series now? We are at a critical inflection point. The 1990’s tough on crime narratives and policies have returned, while the dominant reform strategies continue to fall short and often serve to sustain — rather than disrupt — the status quo. The lack of serious engagement with transformational solutions have trapped generations of Black and Brown communities in a carceral cycle.

Like the maple, leaders are the first to offer their gifts. It reminds the whole community that leadership is rooted not in power and authority, but in service and wisdom.

Issue Brief

Healing begins where the wound was made.

A focus on accountability

The series will focus on the concept of accountability within the criminal legal system, how it has been constructed, why it has been elusive, and how to radically transform the way it’s applied. We are choosing this focus because moments of national outrage about state violence against people of color often lead to calls for accountability and transparency of government systems. While these moments often translate into increased resources, they do not translate into results.

Since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, resources have come in waves in the form of federal investigations, monitoring teams, lawsuits, consent decrees, oversight boards, and funding. While these measures have produced gains, racial disparities in the legal system have worsened across the United States. The longstanding chasms between Black and Brown communities and government grow wider, as demands for accountability remain unrealized in practice. Rarely have we seen our traditional responses lead to systemic change, particularly related to advancing racial equity.

Instead, accountability entities establish opaque monitoring practices that by their very nature send a signal that abuses will remain concealed. This cements the culture of violence, oppression, scarcity, and chaos they were tasked to address.

New York City’s Riker’s Island Jail is one of the more notorious examples. Known for decades of corruption, brutality, and inhumane conditions, Rikers Island has seen numerous oversight and accountability bodies including an external oversight board (Board of Corrections), a consent decree and federal monitoring team, an active City Council, and consistent media attention (Ransom & Pallaro, 2021). Despite all these layers of accountability, and a robust public data warehouse, incarcerated people continue to lose their lives at a record rate, while Rikers remains notoriously one of the most corrupt jail systems in the US (Ransom & Pallaro, 2021). The roots of injustice at Riker’s Island are reflected in its name, as Abraham Riker stole the land from the Lenape People who used it as a site for trade and cultural exchange and his descendent Richard Riker was infamous for abusing the Fugitive Slave Act to send (or sell) African Americans in New York to slaveowners in the South” (Snitzky, 2015).

While Rikers Island is a profound example, it is, unfortunately, not unique. There is a chorus of national calls for accountability and transparency of public safety agencies across the country. These calls are in response to deeply ingrained corruption within police departments, pre-trial justice systems (prosecutors, court systems, jails), and prisons. While the chorus has grown louder, efforts have been underway to shrink and eliminate even the existing national accountability levers, such as the federal Death in Custody Reporting Act (DCRA).

Today, the concept of government accountability and transparency have become mere buzzwords. Minimizing their importance undermines efforts to make good on the promise of governing “for the people, and by the people.”

What do we mean by accountability?

The Merriam-Webster definition of accountability is “an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions.” The common usage of the term reduces it to actions by an individual, but human beings work in the context of a system designed to evade accountability. This is not to minimize the harm that one person can do and the importance of holding that person accountable. However, only by creating accountable public systems can government be in alignment with its stated values. When more weight is placed on the individual level, rather than the systemic and institutional levels, we sustain the abusive status quo across decades, political cycles, oversight entities, and leadership changes.

We seek to explore accountability approaches that take into account one or more of the following three elements: 1) generational impact, 2) centering of truth-telling to change narratives and belief systems, and 3) restorative and healing strategies focused on relationships and communities.

We have much to learn from Indigenous communities who have a long tradition of practicing a circular (rather than linear) approach to accountability. A circular approach considers interconnectivity and does not see the individual alone from their social and natural environment, thereby encompassing these three elements.

In our region, colonization, cultural erasure, and white supremacy have come between us and these important teachings on accountability. But if we do not heal multigenerational trauma, we have not created accountable systems. Instead, we fall into false (and consistently disproven) assumptions that a more transactional policy change approach can create change. When we fail to incorporate all our relations into our solutions, including the historical and intergenerational impacts of those relations, and our atomized policy efforts fail, we blame the victims not the system. This cements this racist status quo and sustains it for generations to come. We must challenge ourselves to break outside of this paradigm and comfort zones.

Indigenous communities think not only of their children’s welfare or even that of their children’s children but also of the welfare of seven generations to come. This cultural timeframe is an essential part of healing process. For justice to be, there must be healing.

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

What is restorative justice?

“Restorative justice seeks a healing for all versus a victory for one. This frequently occurs through a threefold collaborative and dialogical process: (1) storytelling and relationship building, (2) truth-telling and accountability, and (3) reparative action.

It shifts the locus of the justice project from a dependence on systems and professionals to a reliance on the involvement of communities... It moves us from an individualist ‘I’ to a communalist ‘we’ thereby strengthening communities.”

To push beyond our existing paradigm, we are looking at the issue of government accountability through a Restorative Justice lens. At its core, Restorative Justice is about repairing relationships. While it is most often cited as a framework for addressing interpersonal harm, it has also been applied at the institutional and systemic level.

Accountability through restorative justice at the system level

Restorative justice is most often cited as a way to address interpersonal conflict. For example, many schools across the country have started building capacity for using the Restorative Justice circle process as an alternative to traditional school discipline protocols with an eye towards disrupting the school-to-prison pipeline which disproportionally harms Black and Indigenous young people. Restorative Justice has also been used as a pre-trial diversion program to keep young people out of the juvenile justice system, and as an alternative to the traditional court process to address incidents of violence in a more “survivor-centered, accountability-based, safety-driven, and racially equitable” way (Sered, 2017).

While all these entry points for restorative justice are critically important to advancing racial equity it is as important to look at restorative justice as a practice, philosophy, and approach to addressing institutional and systemic level harms.

The accountability that everyone calls for and that proves so transformative – being mindful of our shared roles in harms – seldom reaches beyond the individual level to the institutional, much less to the collective accountability that is the game changer for peoples.

It is no accident that when we first learn about justice and fair play as children it is in the context of telling the truth. The heart of justice is truth telling, seeing ourselves and the world the way it is, rather than the way we want it to be.

Issue Brief

References

A Matter of Life and Death: The Importance of the Death in Custody Reporting Act. The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. (2023, February). https://civilrightsdocs.info/pdf/reports/DCRA-Report-2023.pdf

Colorizing Restorative Justice: Voicing Our Realities. (2020). United States: Living Justice Press.

Davis, F. (2019). The Little Book of Race and Restorative Justice: Black Lives, Healing, and US Social Transformation Justice and Peacebuilding. Simon and Schuster.

Ensign, O. (2018). Speaking Truth to Power: An Analysis of American Truth-Telling Efforts vis-à-vis the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. N.Y.U Review of Law & Social Change, 42(1).

Gomez, J., Wells-Huggins, T., Frank, A., & Andrews, N. (2022, September 2). Truth telling and Palabra: A project at Rikers Island. MILPA Collective. https://milpacollective.org/truth-telling-and-palabra-a-project-at-rikers-island/

hooks, bell. (2001). All About Love. Harper Collins.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Accountability Definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/accountability

Ransom, J., & Pallaro, B. (2021, December 31). Behind the Violence at Rikers, Decades of Mismanagement and Dysfunction. NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/31/nyregion/rikers-island-correction-officers.html

Snitzky, D. (2015, April 15). Slavery and Freedom in New York City. Longreads. https://longreads.com/2015/04/30/slavery-and-freedom-new-york-city/

Sered, D. (2017a). Accounting for Violence: How to Increase Safety and Break Our Failed Reliance on Mass Incarceration. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/accounting-for-violence.pdf